The first thing I look for when checking out a new programming language is immutable persistent data structures. This is an injury I've gotten from Clojure, which has them out of the box. I tend to structure my whole app around these kinds of data structures. They are smart, fast, efficient, immutable and amazing.

In this post, I'll try to make you feel the same way about them.

Axiom: immutability is good

I'm not going to try to sell this one. Because it's a tough sell.

As in, I know a few people that don't like immutable values, and I have no idea how to sell it to them.

Personally, I like to use something that fundamentally eliminates a whole category of bugs from my code.

Sorry. Couldn't resist being snarky. I don't want to trash talk those who don't like immutability. But I just don't get it.

The problem with immutable values is that they're immutable

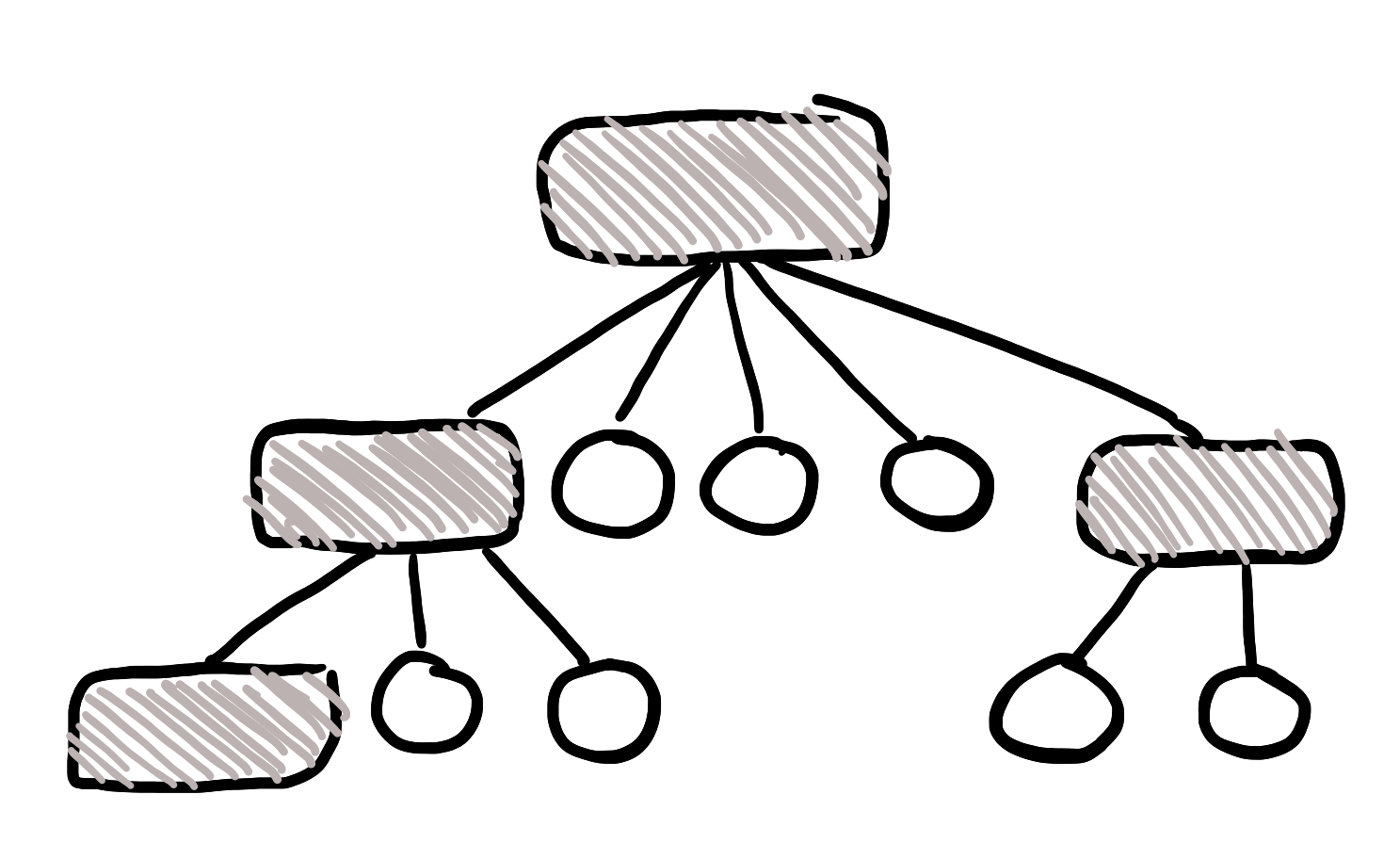

Let's say you have an immutable hash map or something. It's implemented using some kind of tree structure under the hood, like a lot of data structures are.

The problem happens when we want to add a key to this map. The data structure is immutable, so we can't change it!

So, we have to create a whole new copy of everything, an add our new stuff to it.

(Red = new stuff)

A new node was added at the bottom right of the image. And we had to copy all the data in the tree structure, since we can't change the immutable original.

So that's the end of the story, then? Immutability sucks, because you have to copy everything all the time you want to change something?

Well, yes.

But, also, no.

Copy on write - nah

I mean, I'm not gonna diss copy on write completely. There does exist some mildly useful software that leverages it, such as the Linux Kernel.

The whole central and important concept of forking a process in Linux/Unix, relies on copy on write (CoW). When you have a process that uses 11GB of RAM, and you fork it, you have a new process, identical to the original one, with its own copy of the 11GB of RAM. To make the process of forking not horribly tear-inducingly slow, the kernel relies on CoW. The action of forking doesn't actually do anything to those 11GBs of RAM. It's only when you start writing to memory from the fork, that the kernel starts copying and then writing - copy on write - the memory of the original process.

CoW is technically speaking a type of persistent data structure.

However, CoW is at its most useful when the data is mutable. When your data is immutable to the core, you have another option.

That other option is...

Structural sharing - yass

Now this is my kind of persistent data structure.

So.

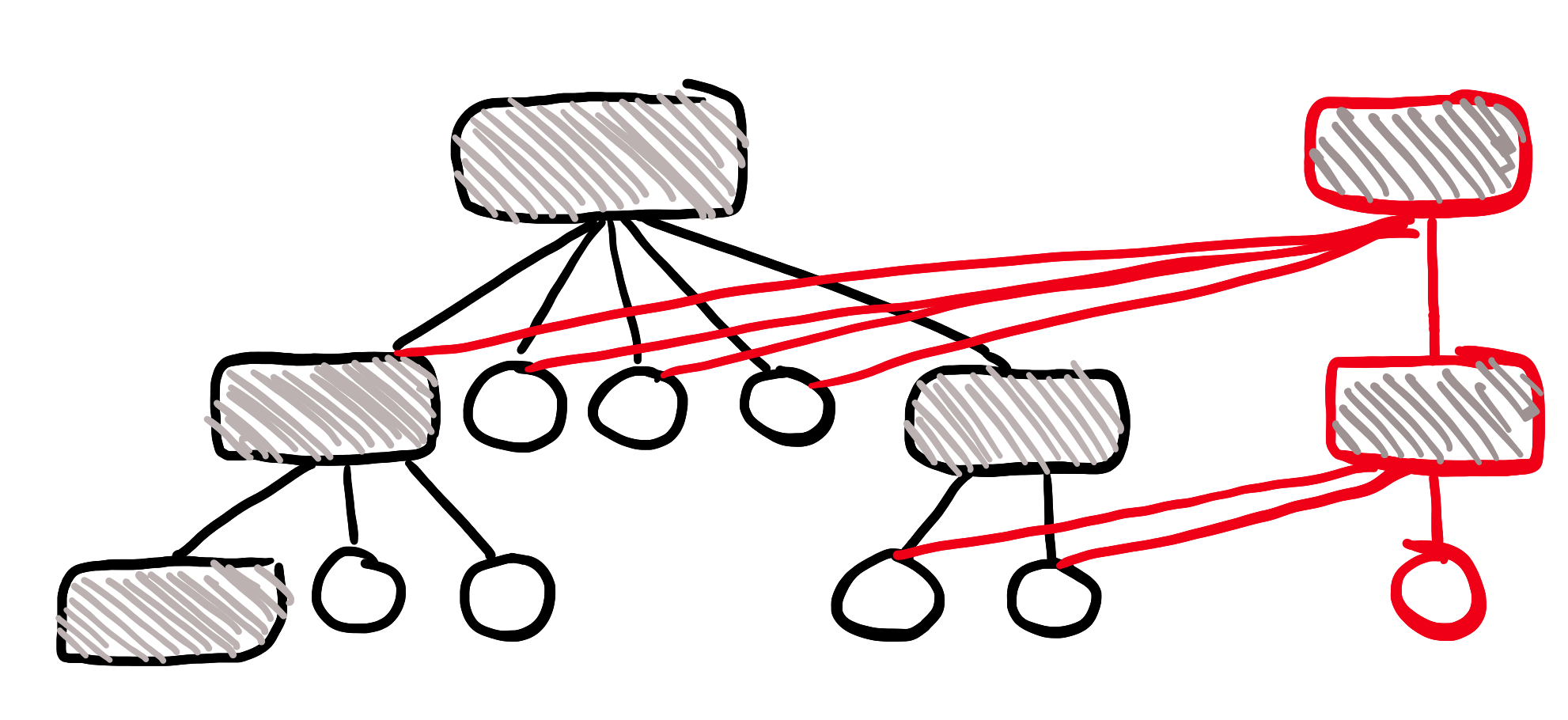

We have this huge data structure. We know that it is immutable. We want to change one little piece of it. What optimization can we run on this process?

Do you see it yet?

The old data structure is immutable. We can just use that!

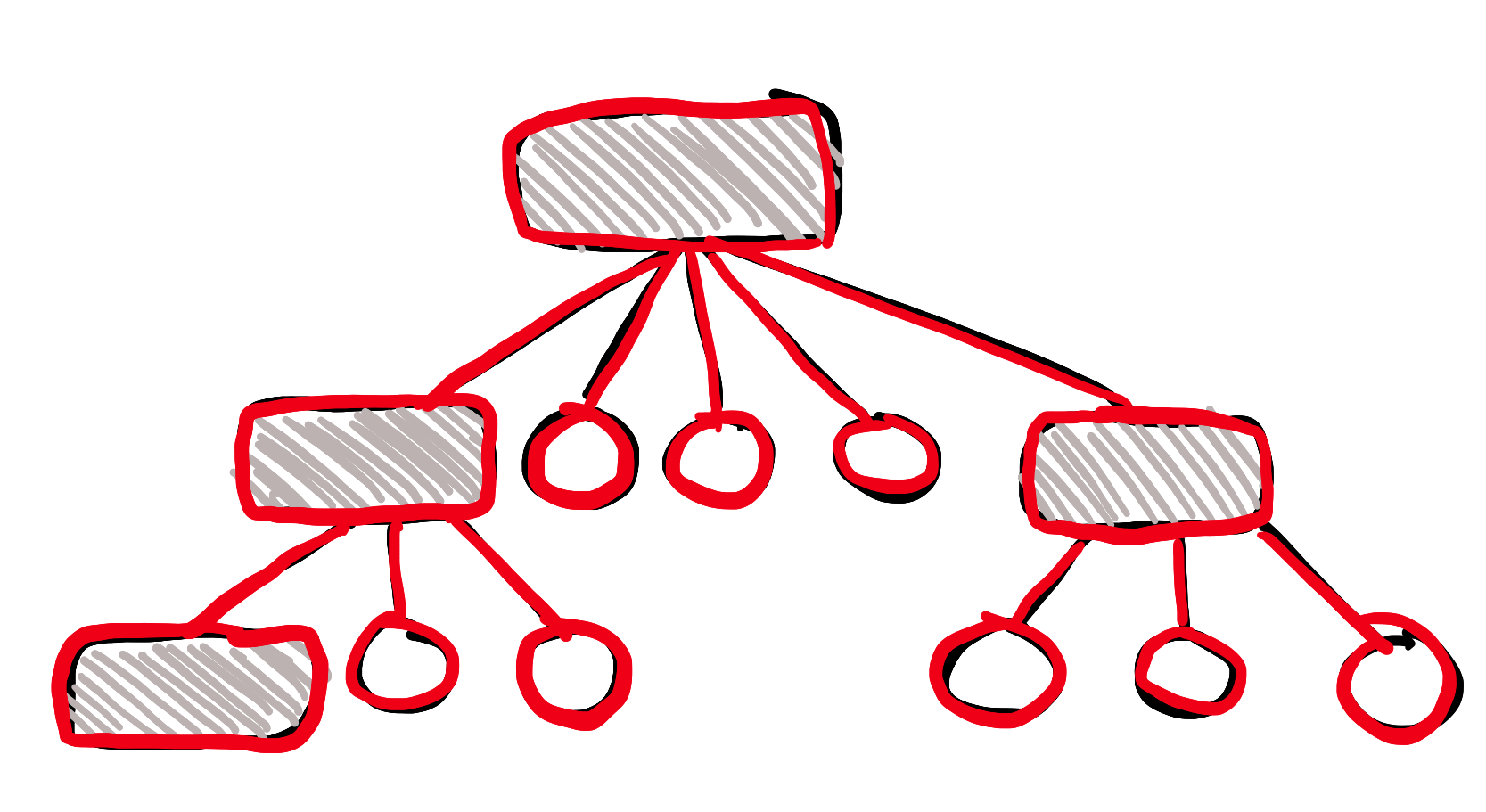

(Red = new stuff)

See what we did? Why copy immutable data?

We just need to create a new root node, a new 2nd node, and a new data node, and then just point to the old stuff! The old stuff is immutable, after all. The whole idea is that it will never change.

You just understood the Clojure state model. The values themselves are immutable. You can have functions that takes an immutable value, that return an updated immutable value. Creating new immutable values is cheap - because you can share almost all of the data with the old immutable value.

Yay!

Clojure does another really cool thing

In the real world, it turns out that if you just have a small map with just a handful of keys, operating on a fancy tree structure can be kind of expensive.

Under the hood, Clojure will do a very cool optimization: if your map has fewer than 8 (I think) items in it, it will just be represented as a normal mutable list under the hood.

When you add an item, Clojure will make a full copy of that list, containing the old items and the newly added item.

Why is that cool?

Well, it turns out that it's actually faster to do it that way, when you only have a small amount of data. Checking a list of 8 items for whether or not your key exists in it, is much faster than having to maintain and balance a binary tree or a b-tree.

Think of it like garbage collection generations. Under the hood, your stuff will be in the "eden" space or "tenured" space. Which is fancy speak for: stuff that is just created and immediately discarded is garbage collected differently than long lived stuff. This happens completely under the hood, as a performance optimization, without you having to do anything special to make it happen.

An other another cool thing!

Let's say you have this function in a tight loop that adds 100s of items to a map, based on a data stream of some kind. Maybe a CSV or a database or something like that.

By default, all maps are immutable, so that means you have to do 100s of potentially expensive operations on the persistent data structures.

However! Clojure has transients.

Transients are a special version of immutable data structures. You first "unlock" it and create a "transient" map (or list or set or ...).

Here's a normal immutable example:

(->> [1 2 3 4]

(reduce

(fn [res curr] (conj res (+ 1 curr)))

[]))

;; [2 3 4 5]Here it is with transients. Notice how we have to use special versions of the functions, like conj! instead of conj.

(->> [1 2 3 4]

(reduce

(fn [res curr] (conj! res (+ 1 curr)))

(transient [])))

;; clojure.lang.PersistentVector$TransientVector@139e6e1dWhoops! We forgot to make it persistent:

(->> [1 2 3 4]

(reduce

(fn [res curr] (conj! res (+ 1 curr)))

(transient []))

(persistent!))

;; [2 3 4 5]This optimization allows Clojure to know that in your tight loop, nobody else will actually use the data structure, so it can be "less fancy" in how it builds it up. And much faster, skipping the entire potential overhead of managing a persistent data structure.

Clojure has pretty cool data structures.